Wenatchee Chambermaid’s Lawsuit Helps Set National Minimum Wage Policy – 3/7/2024

Written by Chris Rader and Margie Jones

Few residents of the Greater Wenatchee area have ever heard of Elsie Parrish – and yet half of our population has felt the impact of this humble woman’s tenacity and search for justice. A lawsuit Parrish brought against her employer, the Cascadian Hotel (owned by the West Coast Hotel Company), rose all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and resulted in the establishment of a minimum wage for women.

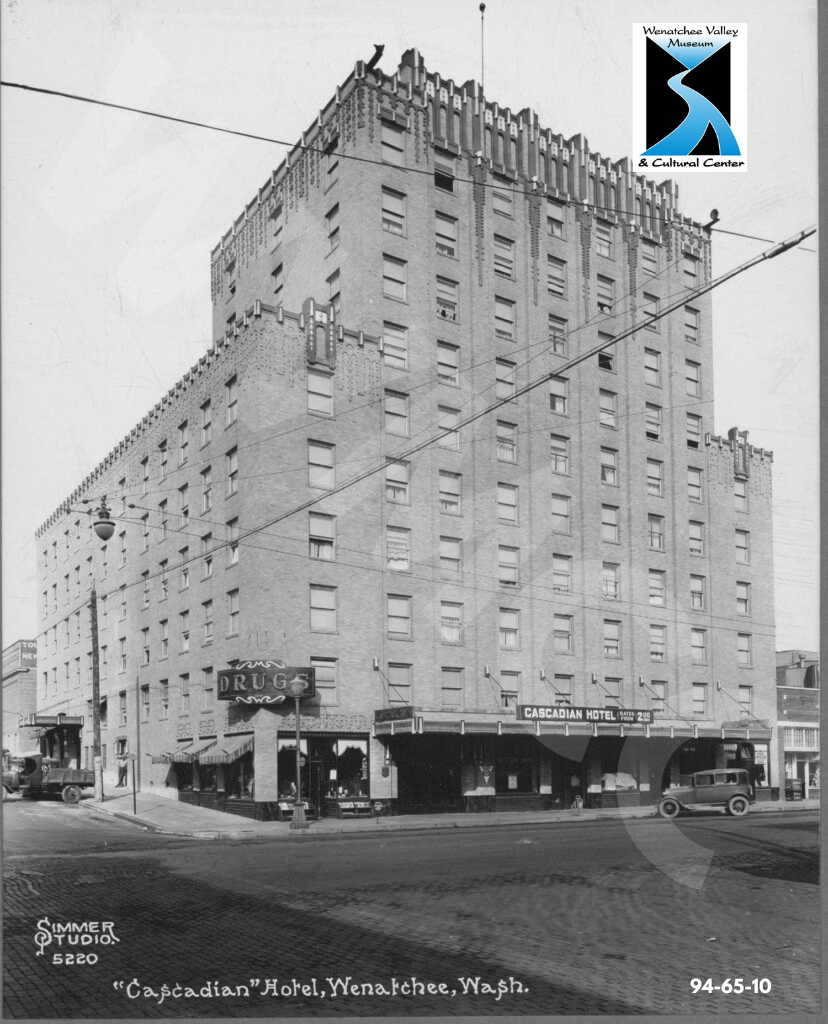

Parrish was a poor white woman who in August 1933 took a job as a maid at the Cascadian Hotel, Wenatchee’s tallest building. The hotel on the of First Street and Wenatchee Avenue featured a ballroom, pharmacy, cleaners, barber shop, and apple sales outlet in addition to 10 floors of hotel rooms. Not much is known about her early life except that she married her first husband at 15 and had six children. When she started at the Cascadian she was married to Ernest Parrish and had become a grandmother.

The Cascadian Hotel, built in 1929, is still Wenatchee’s tallest building. Elsie Parrish worked there from 1933 to 1935. Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center 94-65-10

Elsie made beds, swept floors, cleaned bathrooms, dusted, polished furniture and did all other work required of a maid. She was paid 22 cents an hour; later her pay was raised to 25 cents an hour for a 48-hour work week, or $12 per week. Washington state had passed a law in 1913 that guaranteed women $14.50 a week – but many industries paid little attention to the law, especially after a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1923 found women’s minimum wage unconstitutional.

That 5-4 decision reflected the justices’ corroboration of a 19th-century understanding of liberty, specifically the right of individuals to enter into contracts on terms of their own choosing, called “liberty of contract.” Many felt the Constitution guaranteed this right in Article I, Section 10 and in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Lawyers battled in the courtrooms over whether or not “liberty of contract” meant starvation wages for women and children.

For three decades, the Supreme Court struck down numerous attempts by state governments to improve working conditions or protect consumers – all under the guise of “liberty of contract,” as interpreted from the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Parrish was by no means a legal scholar, but she was determined to be paid what she felt she was owed. When she quit in May 1935, she presented the hotel manager with a bill for $216.19. She told the manager this was the difference between what she had been paid and what she was due, since she had never received the $14.50 per week that was the state minimum wage for chambermaids. The hotel offered to settle for $17.00. “No!” said Parrish, and off she went to find a lawyer.

She hired young Wenatchee attorney C.B. Conner. He based her case on the Washington minimum wage law, which was more compassionate than the federal statute. In November 1935 they appeared by Judge W.O. Parr in the Superior Court of Chelan County. The judge ruled that Parrish could accept the $17 but was not entitled to the $216.19 because the state law was unconstitutional.

Not to be dissuaded, Conner took the case to the Washington State Supreme Court. This court overturned the county’s superior court decision, writing in April 1936: “The very purpose of the act as declared, is to protect womanhood, that the perpetuity of the species is as much a public interest as the fixing of the minimum price of milk…”

The attorneys for the West Coast Hotel were unhappy with this verdict, and took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Five justices on the high court were very conservative and tended to vote in a bloc. It was widely expected that they would uphold two earlier Supreme Court rulings that had struck down minimum wage laws in Washington D.C. and New York. However, in Parrish v. West Coast Hotel, one of the five conservative justices who had voted against the minimum wage laws changed his mind.

Owen Roberts voted with the four liberal justices (among them Louis Brandeis) in support of Elsie’s claim. In the words of the majority opinion:

“What can be closer to the public interest than the health of women and their protection from unscrupulous and overreaching employers? In each (prior) case, the violation alleged by those attacking minimum wage regulation for women is deprivation of freedom of contract. What is this freedom? The Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract. It speaks of liberty and prohibits the deprivation of liberty without due process of law… The exploitation of a class of workers who are in an unequal position with respect to bargaining power and are thus relatively defenseless against the denial of a living wage is… detrimental to their health and well-being.”

Elsie Parrish’s victory on March 29, 1937, signaled the end of the controversy over minimum wages for women. In fact, a few days later President Franklin D. Roosevelt remarked that minimum wage laws should not be confined to women; he asked Congress to pass a law for all workers. Several months later such a law was passed, guaranteeing all workers the sum of 50 cents an hour. The Wenatchee chambermaid had opened the door.

At the time of the decision, Elsie was working at the Model Laundry in Omak. She said she was happy with the results of her lawsuit, and intended to continue working. There was some indication that she would have been willing to go out and speak about her experience, but no one asked. Elsie Parrish disappeared from history – but her fight for justice had far-reaching and long-lasting results.

Editor’s note: Margie Jones wrote an article in the Summer 1988 Confluence titled “Elsie Parrish: A Woman History Forgot.” Jones kindly gave permission to the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center to include excerpts from that article in this story.

This story was originally published in Confluence Magazine in the Summer edition of 2008. In an effort to preserve these stories, the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center will be posting these stories on the museum’s official blog.

Become a member to get a free copy of Confluence Magazine. Learn more about how to become a member here!