Wenatchee Has the ‘Biggest Little Circus in the World’ – 07/23/2024

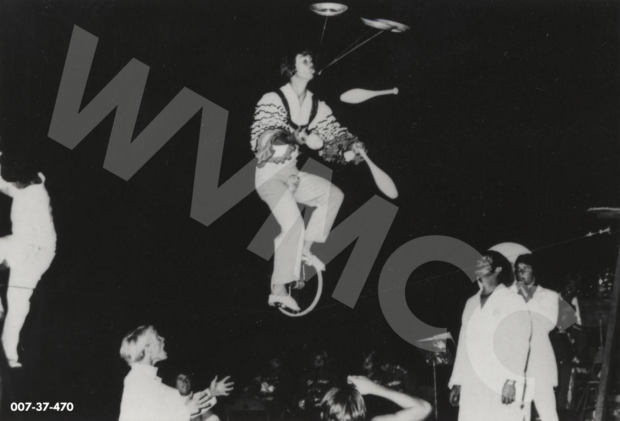

Photo Caption: A young man juggles and balances plates as he rides a unicycle on the tight wire in the late 1960s. Source: Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center #007-37-470

Written by Chris Rader

From city parks and school gymnasiums to Canadian ice arenas, the Seattle Kingdome and Los Angeles County Fairground, audiences of all sizes and ages have loved the Wenatchee Youth Circus for 65 years.

What is now a nonprofit organization began in 1952 as an H.B. Ellison (now Orchard) Junior High School tumbling club. That year several dozen boys and girls, under the direction of teacher Paul Pugh, perfected somersaults and handsprings, balanced on teeter boards, and leapt from spring boards over pyramids of other students. They performed at junior high assemblies and provided halftime entertainment for Wenatchee High School and Wenatchee Junior College basketball games.

The following year Pugh took the club to perform in Quincy, Chelan and Ephrata, in addition to shows in Wenatchee to increasingly larger audiences. A trampoline and low wire were added to the modest collection of equipment.

“Joe Earhart made a tight wire about two feet off the ground,” recalled John White, who was in Pugh’s home room at Ellison and a member of the tumbling team for its first three years. He is now a State Farm insurance agent in Wenatchee. “I could walk on it because I lived on the other side of the train tracks and walked on the train rails all the time.” White said the low wire was a homemade contraption made from 2x4s and 4x4s bolted together to make two pedestals, with a wire running between them.

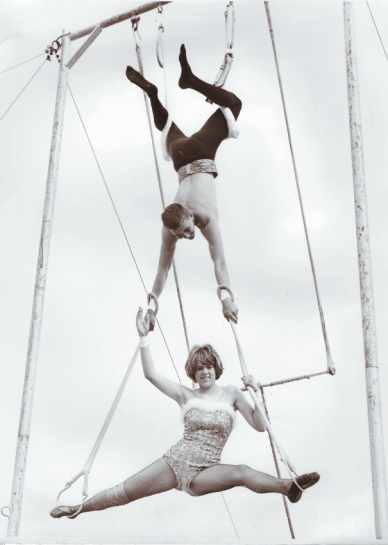

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. The Wenatchee Youth Circus performed during the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. Crowds marveled at acts of skill such as Gail Meek and her partner on trapeze.

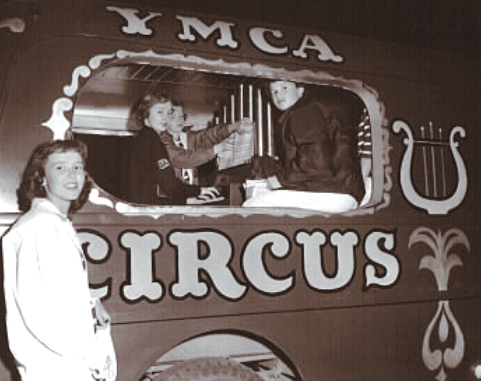

In 1954 the Wenatchee YMCA offered to sponsor the program; it became known as the Wenatchee YMCA Circus. More acts were added and the travel schedule grew. Pugh acquired a battered old truck at a sheriff’s sale for $26 to haul costumes and equipment. When the circus took to the road, parents of the performers volunteered as chaperones and helped with meals and setup.

By 1957 the circus had become a year-round endeavor, with practices held from fall to spring to prepare for a summer tour of the Northwest and a trip to Alaska. In Anchorage, Wenatchee children aged three to 17 performed before crowds totaling 11,000 despite the cancellation of two shows because of rain.

The local Shriners sponsored the engagement, meeting the troupe at the airport at 4:45 a.m. and entertaining the kids when they weren’t performing: driving them on sightseeing tours, taking them on plane flights, donating snacks and giving them a special party. (The old truck, driving equipment up from Wenatchee and delayed by road washouts, barely made it to Anchorage in time for the first show.) The YMCA Circus was featured in the local newspaper every day and the kids appeared on Anchorage television.1

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. Crowds marveled at acts of skill such as Gail Meek and her partner on trapeze.

Circus had animals

Before leaving for Anchorage, the YMCA Circus had purchased a boa constrictor named Ophelia. An Anchorage man who was disbanding his wild animal show admired Paul Pugh and gave him a South American ocelot and Florida bobcat to keep Ophelia company.2

For the next five years or so, the circus incorporated several animals into its acts. Circus member Bob Ingle trained his shaggy little black dog, Peggy, to climb ladders and leap through a burning hoop. His brother Dale taught a rhesus monkey to do some crowd-pleasing tricks. Two other monkeys, an anaconda snake, a duck named Waddles, BoDee the baby baboon, and a horse were also part of the circus until 1963 when it became too hard to care for them over the winter. “Can you imagine trying to coax a family into keeping a constrictor in the basement from September until May?” Pugh asked a reporter from Alcoa News.

In 1962 the youth circus separated from the YMCA and incorporated as a nonprofit, with a board of directors. YMCA president William McHaney said, “The feeling is, the success the circus is gaining makes it a complete entity of its own.” The first board members were James O’Connor, president; Paul Pugh, Chet Endrizzi, Margaret Adams, Mrs. Doug Griffin, Walter Barnhart, Ed Meek, Clair VanDivort and Robert Valaas.3

By this time the Wenatchee Youth Circus had gained national attention. A six-page article brimming with color photos appeared in the Feb. 3, 1962 Saturday Evening Post. The circus now had 24 acts, a roster of about 85 kids, a brass band, and a touring schedule of some 4,000 miles annually. Its holdings included an old school bus, three trucks, two trailers and several tons of equipment – all worth $60,000.

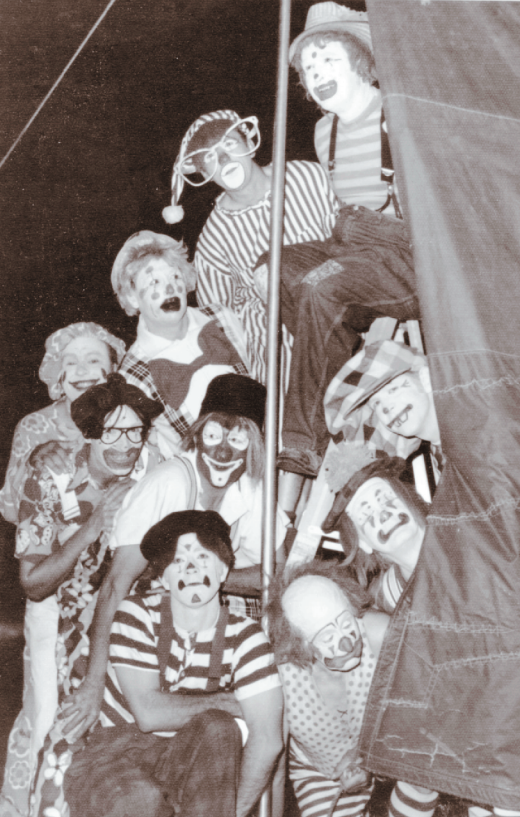

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. Pugh and Endrizzi trained hundreds of child clowns in decades of youth circus work.

The circus was invited to give a series of performances at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. A news reporter described some of the acts he observed in a warmup show at the Kent High School stadium:

Daring feats performed on the high flying trapeze, desperate balancing on the 27-foot high wire, frantic somersaulting on the bouncing trampolines, juggling, fire eating, trained dogs and monkeys, lots of funny clowns, and good circus music with a 20-piece circus band and air calliope.

The reporter highlighted some of the performers: Terry Ogle, 19, Pugh’s assistant and a star flyer on the trapeze; Jim Weythman, 17, teeter board, swinging ladder and catcher on the flying trapeze; Margaret Adams, 16, juggler and fire eater; Dan Barnhart, 16, ringmaster and whip cracker; Glenn White, 17, inclined cable, juggling, high wire and revolving ladder; twins Sharlene and Karlene Cearlock, 15, who appeared on high wire, webs and ladders, trapeze and other acts; and fearless Barbie Meek, 8, walking on the high wire. 4

The clown acts were always popular with audiences. Pugh assumed the persona of Guppo, painting his face white and wearing a striped shirt and plaid vest with a bright orange wig and huge clown shoes of red and white. He and other adults, including Chet “Chula” Endrizzi, Dr. Ed “Luko” Cadman, board president Harold Ottosen and later board president Rocky Thomas, would work the stands and goof around in the ring between acts in order to give the younger performers a chance to change outfits. A perennial favorite was the clown car, a blue Volkswagen that Rocky the Clown would drive into the ring.

Ringmaster Guppo asks him if he has any friends. “Sure!” replies Rocky. “Well, line them up here in the center of the ring.” The audience laughs as the first 20 children, many of them local youngsters recruited from the bleachers by the clowns, climb out of the car. More and more kids tumble and climb out of the little car until they all stand outside. The record number is 45, and they’re trying to beat that!5

One of his favorite props, received from fellow Whitman College alumnus and mentor Harper Joy, was a billiard cue rigged up to magically balance three balls in the air. He and Chula taught countless children to use this over the decades.

Even stunts that have been around forever drew hearty guffaws when performed by adult or youth clowns. In a show in the West Seattle Stadium in 1962, Guppo formally presented Miss West Seattle (Sandra Gallagher) with a potted plant. Of course, as she lifted the plant from his hands, he squirted her in the eye. She went along with the gag as 5,000 audience members laughed and cheered.

Parent chaperones help out

Paul Pugh’s wife Kay traveled with the youth circus for its first 22 years, until their divorce in 1974. Other parents took turns accompanying the performers to shows all over the West, from Alaska and British Columbia to Oregon, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana.

Jim and Pat O’Connor offered their large yard on Pershing Street for a staging area and off-season practice field for the circus during the 1960s. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, when their sons Larry and Gary were performers, Jerry and Louise Harlow let circus members practice in their back yard on Burch Mountain Road. Jerry also did much of the mechanic work for the circus and Louise made costumes for more than 20 years.

Courtesy of The Wenatchee World. Shirley Shelton shows the skunk and bear costumes she made for the Wenatchee Youth Circus.

Shirley Shelton was the wardrobe mistress and costume designer for the Wenatchee Youth Circus in the 1960s and ‘70s. “I try to design a costume so a child can put it on and forget it,” she told The Wenatchee World. “It can’t bind or snag. The kids have fast costume changes that really amaze people, so they have to have costumes that can take it.” Shelton also created animals from furry woolens and fake furs to be used in clown acts. One was a bear head that covered an old motorcycle helmet. Another was a skunk made to cover a gallon bleach jug; its pouring spout made a good snout base.6

In the later 1970s and ‘80s, circus moms Nell Towne and Louise Harlow were in charge of costumes: designing them, buying material, supervising other seamstresses, and storing and caring for them all. By 1988 it took 20 trunks to hold all the costumes. They and the kitchen equipment, including freezers, were transported in a 40-foot van, while the 90 to 100 performers and 10 chaperones rode to out-of-town gigs in two charter buses with their luggage and sleeping bags.

Keeping the performers fed was a monumental task. Gwen Endrizzi was queen of the cook house for 36 years (see following article), serving an estimated 180,000 meals to hungry performers and chaperones each season.7

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. Performers demonstrate the “human pyramid” in the 1990s. Walking the high wire is a feat in itself, but it’s especially hard when you’re balancing a passenger!

Like so many WYC parents, Joe Anderson’s mom, Jewel, also assisted with costumes, kitchen duties and chaperoning. “Without the involvement and support of parents, the youth circus wouldn’t have happened,” he affirmed.

Paul Pugh married Karen Peart Day in 1975 and she became part of the circus, too. She served on the board for many years and traveled as a chaperone, juggling circus trips with a fulltime job in banking. “Gwen and Chet Endrizzi, Mary and Roy Reinstra, Paul and I got to be great friends on all those bus trips,” she said.

Performers work hard

Participants in the Wenatchee Youth Circus, then and now, do more than perform their acts in front of crowds. At each stop, the kids and a few adults spend about three hours unloading equipment, setting up tents, pounding stakes, setting up block and tackle and riggings, connecting pieces of the bandstand, hooking up the portable generator to strings of electric lights for night shows, and erecting the rigging for trapezes and high wires.

“Responsibility teaches these kids a great deal,” Pugh told Alcoa News in September 1963. “And let me tell you, there’s a pack of responsibility on the shoulders of a rigging crew – average age 14 – assembling a trapeze or high wire to bear the bodies of their own buddies.”

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. All youth circus members helped set up for every performance. This photo from 1976 shows the teamwork necessary to set up long poles for trapeze rigging.

Over the years, Pugh managed the young performers

“With a fine balance of firmness and affection. Any child who really wants to be in the circus can join if he is willing to practice three nights a week and every Saturday afternoon all through the winter. Little by little the natural agility and enthusiasm of a novice are transformed into skill and confidence. Pugh watches for latent talent and guides the youngster toward the act which will make the best use of his skills. “You can’t push them,” the director says. “When they’re ready to try something new, they’ll let you know.”8

“Everyone was in their place, knew what they had to do,” recalled Terry Ogle, who joined the circus at age 12. “We’d work as a team, on the high wire or whatever. It was a unity that’s difficult to explain to people nowadays.” Ogle became an expert on the high wire and trapeze; Joe Anderson was one of the catchers on the trapeze who would grab Ogle after he executed a double backward somersault.

Mike Salmon, in the 1960s, played percussion in the circus band, then became a clown and learned to perform on the hire wire and inclined cable. He remembers Pugh stressing that the performers, though kids, were professionals – and held them to high standards of safety. “Check the rigging. Make sure the guy wires are tight and secure on the high wire. Check the net and tie downs, and keep an eye out for anything that doesn’t look right, even if it’s not in our area.”

Salmon said giving live performances was always fun, including the occasional ad lib to cover a problem. “You’d be jumping on the trampoline, and suddenly your costume would split out. You’d quit jumping, get down, and somebody else would get on the tramp while you made a dash behind the curtain!”

Cory Evers was 14 when he told a reporter for Discovery Magazine in fall 1985, “Sometimes when I’m juggling, I look up and see people watching with their mouths open. It’s a thrill to be part of that.”

That national magazine article also quoted circus alumnus Lynn Watson: “It takes a lot of courage to do our acts. I rode a unicycle on the low wire, but when I took it up to the high wire an hour and a half passed before I tried it. And the only reason I did was because the cook tent was open, and I wanted to eat!”

Courtesy of Karen Pugh. Performers in dazzling costumes showcase balance and coordination on the Roman ladders.

In 65 years of touring, the Wenatchee Youth Circus has had very few accidents. The worst was in 1967 in John Day, Oregon, when 15-year-old aerialist Julie O’Connor fell 18 feet from a trapeze pedestal to the ground, landing on three inches of sawdust. She was whisked to the local hospital with a concussion (but no broken bones), then flown to Portland’s Providence Hospital, where she regained consciousness two days later. Pugh later determined she had been shaken off balance when a knot slipped in one of the taut guy lines that rigidly braced the pedestal. After a few days’ rest, Julie rejoined the circus in Los Angeles – though Pugh temporarily kept her to the low wire and bounding rope.

Julie’s father Jim, an attorney, was a major booster of the Wenatchee Youth Circus. In addition to letting the performers practice in the O’Connor yard, he offered free legal and financial advice to manager Pugh and established a scholarship fund. Each year since 1967 the fund has awarded $500 in college scholarships to some 250 graduating seniors who have spent at least three years with the circus. Sales of printed programs augment the endowment and its interest earnings.

The circus has never been a big money maker. Pugh ran it on a shoestring, not wanting to charge the out-of-town venues too much for the shows and keeping the performers’ registration fees low. “Operating on a percentage basis – usually 70 percent to the circus, the rest to a sponsoring group such as Rotary or Kiwanis – the circus does well to break even. But it reaps a dividend in the joy it brings to the young performers.”9 This attitude prevails today. It currently costs just $25 for a single person or $30 for a family to join the circus, plus $5 for insurance.

Pugh continued as Wenatchee Youth Circus director until about 2010, though he stopped driving the bus and relied more and more on his assistants. Brandon Brown is the organization’s current director. Information, including schedules and registration forms, may be found at www.wenatcheeyouthcircus.com.

“The secret of our circus is that everyone helps each other,” Pugh told Discovery Magazine in fall 1985. “There are no stars.” Well, no stars except the WYC’s beloved founder and longtime director, Paul Pugh.

ENDNOTES

- Wenatchee Daily World, Aug. 25, 1957.

- Donn and Nancy Moyer, “A Tribute to Paul “Guppo” Pugh and the WYC,” c. 2002.

- Wenatchee World, Feb. 16, 2012.

- Kent News-Journal, Aug. 15, 1962.

- Small World Magazine, May 23, 1971.

- World, Oct. 22, 1972.

- Kellogg (Idaho) Evening Star, July 29, 1964.

- “Greatest Little Show on Earth,” Saturday Evening Post, Feb. 3, 1962.

- Ibid.

OTHER SOURCES

Scrapbooks donated by Karen Pugh to Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center.

Selina Danko conversations with John White, Joe Anderson, Terry Ogle, Sam Thacker, Mike Salmon, Linda Haglund and Kayla Taylor in December 2016.

Chris Rader conversations with Dave Pugh, Jon Pugh and Joe Anderson in January 2017.

This story was originally published in Confluence Magazine in the Spring edition of 2017. In an effort to preserve these stories, the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center will be posting these stories on the museum’s official blog.

Become a member to get a free copy of Confluence Magazine. Learn more about how to become a member here!

Interested in keeping a photo copy? Learn more about our photo archives and request your own copy below.