Chinese Mined Around Wenatchee – 5/24/2024

Caption: This painting by the late Wenatchee artist Walter Graham depicts Chinese miners with a sluice box and pan, searching for gold on the Columbia River. The painting can seen at the Rocky Reach Visitor Center.

Written by Chris Rader

Many, if not most, of the placer miners working the Columbia River in the 1860s through the 1880s were Chinese. Some had been brought to California, Alaska and Oregon as laborers in the salmon industry; others worked on U.S. and Canadian railroads. They were not always treated well, and many ran away from the work camps and started hunting for gold.

Henry Livingstone, one of the men who discovered gold on the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1857, recalled decades later that hundreds of Chinese miners had settled on the Columbia River above Priest Rapids by 1856. Chinese in the vicinity of Wenatchee worked productive gravel bars at Bridgeport, Orondo, Entiat, across from Chelan Falls, and Rock Island (and points in between). Numbers are uncertain, though newspaper estimates of 5,000 Chinese mining along the Columbia between 1860 and 1870 are surely exaggerated. Historian John Esvelt suggested 1,500 as a more reasonable number of Chinese mining the Columbia above Walla Walla during that decade (1).

A.J. Splawn, a teenager driving cattle in the 1860s from the Yakima Valley to the Cariboo mines of British Columbia, encountered many Chinese miners along the way. He wrote of a large camp on the east side of the river at today’s Rock Island where a Mr. Wing operated a trading post. About 100 Chinese had purchased this gravel bar from white miners. Splawn carried many a buckskin bag of gold dust to be deposited to the Chinese miners’ bank account in Portland in 1864-65 (2).

At Rock Island, the miners worked claims on both sides of the river. On the west side was a six-mile ditch that conveyed water from Colockum Creek to a large sluice box on the shore of the Columbia. The late Daniel Meschter, a respected Forest Service mining engineer who did exhaustive research on Wenatchee-area mining history, wrote that the ditch was probably dug by a man named Warren in 1871. Chinese placer miners then used the water source and it came to be known as the Chinese Ditch. Meschter visited the site with packer/ mountaineer “Colockum Bill” Hansen, who pointed out the mulberry trees along the ditch. This fruit-bearing species is indigenous to Asia; Hansen theorized that the trees might have been planted by Chinese. Remnants of this ditch can still be seen today.

Another early ditch in the vicinity used water from Stemilt Creek to flow through sluice boxes along the Columbia, about half a mile above the current Alcoa aluminum plant. Wenatchee historian Al Bright stated that Chinese built this ditch, then abandoned it around 1872. Mr. Lockwood and other settlers improved it began using its water to irrigate their homesteads and the ditch became known as the Lockwood Ditch.

Chinese miners aim a monitor nozzle to direct water for sluicing a placer deposit in Idaho. Many white miners learned placer mining techniques from the Chinese. Source: Discovering Washington’s Historic Mines, vol. 2, 2002.

Some Chinese working placer deposits along the Columbia traced very fine “flour gold” up Squilchuck Creek, where they discovered the silicified intrusions within the sandstones of the Chumstick Formation on the northwest side of the canyon. Thus began the first hardrock mining in this area, according to geologist Charlie Mason.

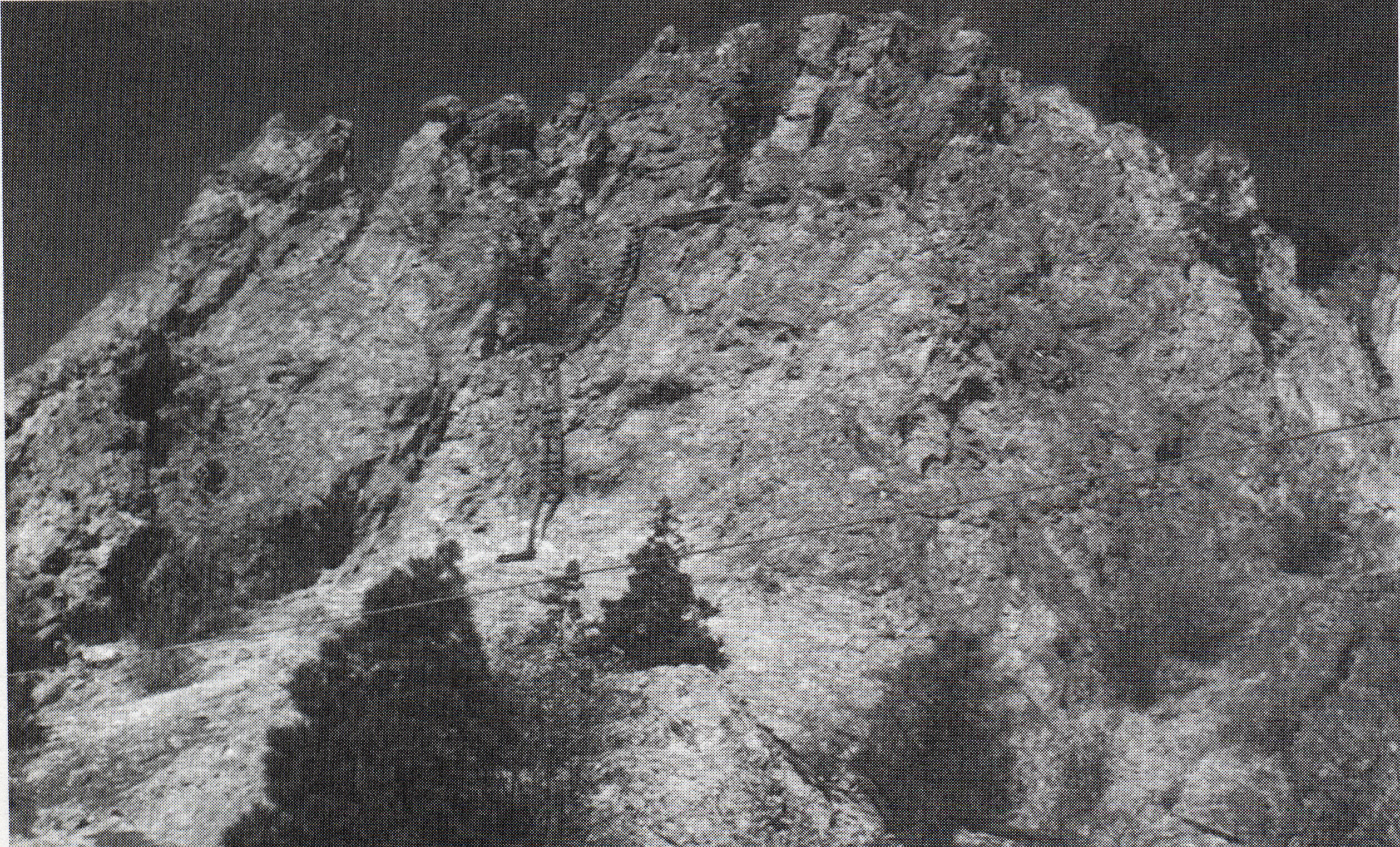

“True, it was limited in scope. The Chinese miners erected ladders on the sides of the formation, climbed up and broke off fragments of the enriched sandstone. Companions waiting below would gather up the pieces, crush them, then pan out the flour gold in the stream flowing through the canyon. Ladders, evidence of their labors, are still visible attached to the rock inclines of the formation (3).”

Historian Richard Steele described in 1904 the remnants of another large Chinese mining camp on the east side of the Columbia across from the mouth of the Chelan River, at the foot of today’s Beebe Bridge.

“It was built mainly of cedar boards split from the log, like shakes, pegged against upright posts, and roofed with logs and brush. At present nothing but the shells of these huts remain. In this early settlement there was a store. It was the first business enterprise in the country; the proprietor was a Chinese merchant. To the Chinese workers along the river he supplied goods, and he made considerable money. A pack train of forty horses he owned with which he brought in his miscellaneous assortment of English, American and Chinese merchandise. It is stated that no stranger ever appeared at this store who was not made welcome by the old Chinese merchant (4).”

Other historians say this village included vegetable gardens, opium dens, gambling houses, a laundry and a church. The Chinese miners were industrious and frugal. Many of them sent their earnings back to relatives in China. With few Chinese women living in the U.S., it is natural that some of the men became interested in the native women. Indian men were not happy about this, and conflict sometimes ensued. Splawn recalled an encounter between a Chinese worker and two Columbia-Sinkiuse Indians in 1865.

“When we reached the Columbia, about eight miles below their camp, the Chinamen, who had always been in the rear, now rode in front. Shortly after, I saw two Indians coming towards us. When they met the Chinamen one of the Indians began to beat the yellow men with the elkhorn handle of his riding whip, while the other Indian came straight for me….The Indians rode away and I gathered up my Chinamen, badly bruised, but no bones broken. When at the camp, the bunch of Chinese saw their mutilated brethren, a howl went up like the noise from a flock of wild geese fired into suddenly (5).”

Chinese miners built ladders to access ore on the rock face above Squilchuck Creek. These ladders can still be seen today, just left of center in the above photograph. Source: James Marr, Jr., The Life Times of the Holden and Lovitt Mines, 1994.

Indians attacked the Chinese at their Beebe Bridge village in approximately 1875, killing some villagers and causing others to temporarily abandon the village. That same year, several miles downstream, the Indians found a group of Chinese working on a bluff along the river. They surrounded the bluff and trapped the miners, forcing them to jump to their deaths or be killed. An estimated 300 Chinese died. Around the same time, Indians killed 10 miners below Rock Island (6).

The Miller-Freer Trading Post at the mouth of the Wenatchee River was a friendly place for Chinese miners to do business. Proprietor Sam Miller kept a ledger of purchases by pioneers, surveyors and other travelers, Chinese, and Native Americans.

“The largest group was Chinese with over a hundred names like Hie Tom, John China, Ah Chung and Ah Suyin. They bought pants, shirts and shoes, shovels, tin buckets and pans, canvas, needles, thread and quicksilver (they were the first miners in the valley to use mercury to extract gold). They also bought food: prunes, canned oysters and lobster, tea and coarse brown sugar – whiskey, flour and rice, tobacco, bacon beans, “China oil” and “China cabbage,” salt, lard, ginger, cinnamon, pepper and “fresh shrimps” [probably crawdads]. They always paid their bills promptly and almost always with cash or gold dust, though on one day Sam Miller gave Ah Suyin $3 credit for three chickens (7).”

It is likely that many of the Chinese did “group buying,” with the best English speaker making the purchases.

Chinese miners in the 1870s outnumbered whites two to one in the Swauk Mining District, the first to be formed in Washington Territory. This district originally included both sides of today’s Blewett Pass, along Swauk and Peshastin creeks where much gold was being recovered.

An artist’s rendering of a Chinese camp in the early days of the gold rush in the United States. Two large Chinese mining camps flourished on the Columbia River near Wenatchee in the late 1800s: across from Chelan Falls and at Rock Island. Source: Discovering Washington’s Historic Mines, vol. 2, 2002.

Anti-Chinese sentiment grows

Prejudice against the Chinese was growing in the United States in the late 1870s. In 1882 Congress passed a national Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting Chinese to enter the country but allowing those already here to stay. Tacoma city officials and labor union members expelled more than 200 Chinese from that city in 1885. Similar efforts were made in Seattle and Olympia the following year but did not succeed, as local citizens came out on the streets to protect Chinese from the mobs (8).

A reorganizational meeting of the Swauk Mining District was held on May 7, 1884. The primary reason appears to be to exclude Chinese miners from the district. Article four of the minutes read:

“Resolved that all Chinamen within the boundaries of Swauk Mining District shall leave and shall not be allowed to work or hold any mining ground in the District and that no Chinaman shall hereafter be allowed to come into the same for the purpose of mining, and that a notice be served on those now in the limits of the district to leave at once.”

The resolution was carried unanimously. However, no provision was made for enforcement of the measure, and it appears that many Chinese were tolerated in spite of it (9).

On March 8, 1892, Wenatchee Advance newspaper publisher Frank Reeves convened a public meeting to discuss the “Chinese problem.” Those in attendance voted unanimously to exclude “Mongolians” from Wenatchee, with only one abstention, hotel owner Noah N. Brown. They agreed that they would not resort to violence. A committee of six, chaired by Mike Horan, was elected “to see that no Chinamen were permitted to locate within the limits of Wenatchee,” with its power confined to “honorable, legal and lawful means….

When it was suggested that it might be found a difficult matter to exclude Chinese by honorable, legal and lawful means, it was ominously met by the frank statement that if these failed, another mass meeting could be easily assembled and the committee authorized to adopt another method (10).”

One reason for this dark chapter in Wenatchee’s history was given by fruit grower E. Wagner. He noted that. Chinese miners were earning $1.50 a day but sending their earnings back to China; therefore, the whites wanted to get rid of them. In 1893, a group of business leaders went to Sam Gehr, the miller, and threatened to burn him out if he didn’t stop selling flour to the Chinese. He complied (11). By 1898 only two Chinese miners remained in the Wenatchee area, panning gold at Stemilt Creek (12).

ENDNOTES

- John P. Esvelt, “Upper Columbia Chinese Placers,” The Pacific Northwesterner, vol. 3, 1959.

- Mary Gaylord, Eastern Washington’s Past: Chinese and Other Pioneers, 1860-1910, 1993.

- Charles Mason, The Geological History of the Wenatchee Valley and Adjacent Vicinity, 2006.

- Richard F. Steele, A History of North Washington, 1904.

- Maureen E. Brown, Wenatchee’s Dark Past, 2007.

- Ibid.

- Rod Molzahn, “Chinese miners came and went in a flash,” The Good Life, June 2010.

- Rod Molzahn, “Whites zealous in expelling other cultures,” The Good Life, March 2010.

- Discovering Washington’s Historic Mines, vol. 2, 2002.

- Steele, op. cit.

- Eva Anderson, Pioneers of North Central Washington, 1980.

- Brown, op. cit.

This story was originally published in Confluence Magazine in the Winter edition of 2012-13. In an effort to preserve these stories, the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center will be posting these stories on the museum’s official blog.

Become a member to get a free copy of Confluence Magazine. Learn more about how to become a member here!